Child sexual abuse images and online exploitation surge during pandemic

Michael Oghia was on a Zoom videoconference with about 20 climate activists last week when someone hijacked the presenter’s screen to show a video of explicit child pornography involving an infant.

“It took me a moment to process it,” said Oghia, advocacy and engagement manager at the Global Forum for Media Developments. “At first I thought it was porn, but as soon as it clicked I shut my computer. What the hell did I just see?”

Oghia’s call had been “zoombombed” with footage of child sexual abuse. He’s unsure whether it was a video or a livestream, but it left him feeling traumatized and unable to sleep.“It goes without saying that the real victim is the baby, but I can completely understand why social media content moderators develop PTSD,” he said.

Oghia’s experience is an extreme example of what people who track and try to stop child abuse and the dissemination of child pornography say is a flood of child sexual exploitation material that has risen during the coronavirus pandemic.

And with tech companies’ moderation efforts also constrained by the pandemic, distributors of child sexual exploitation material are growing bolder, using major platforms to try to draw audiences. Some platforms are warning users that when they report questionable or illegal content the company may not be able to quickly respond.

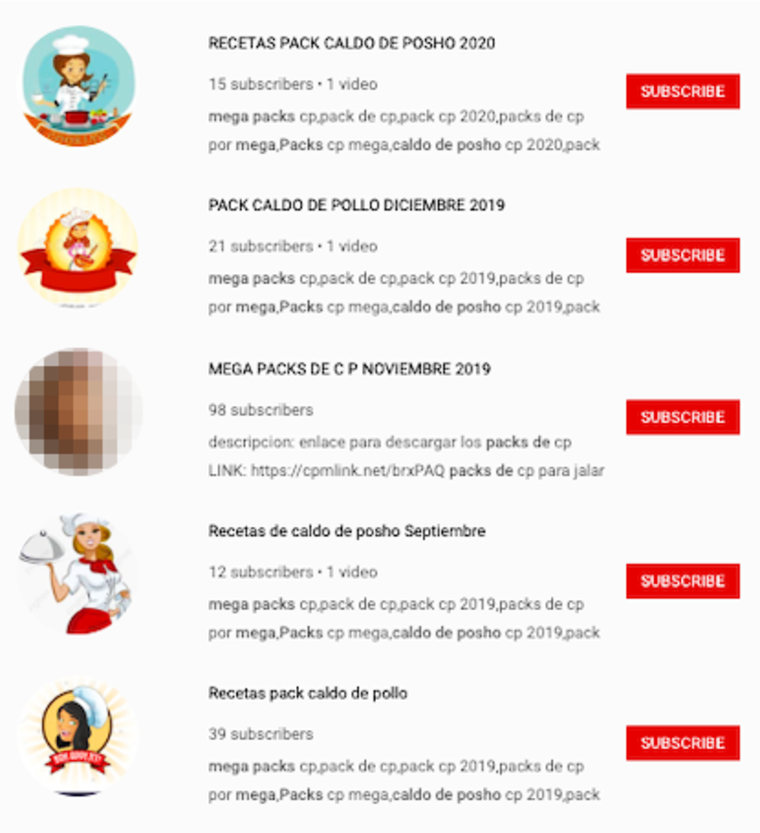

Distributors of child sexual abuse images are trading links to material in plain sight on platforms including YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram using coded language in an effort to evade the companies’ detection tools, according to child safety experts and law enforcement. At the same time, reports of child sexual exploitation activity to cybertip hotlines are up by an average of 30 percent globally, according to InHope, a network of 47 national cybertip lines.

Reports to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, the organization that receives cybertips in the United States, including from all of the Silicon Valley technology platforms, have more than doubled from 983,734 reports in March 2019 to 2,027,520 reports this March. A significant chunk of the new reports are made up of a small number of videos that went viral, according to John Shehan, vice president of the center’s exploited children division.

Zoom said it was looking into what happened on Oghia’s call, but any report of child abuse on its platform is “devastating and appalling” and prohibited by its policies. The company said that it uses a mix of tools, including automated ones, to proactively identify accounts that could be sharing child sexual exploitation material and that it notifies law enforcement where appropriate. Zoom also now defaults to password protection for all meetings. Oghia’s meeting did not require a password.

The incident came at a time when popular social media, video and messaging platforms have been flooded with child sexual exploitation material, experts told NBC News. The COVID-19 pandemic means that people are spending more time online at home, leading to a greater demand for this type of content.

How the coronavirus exposed the country’s weaknesses

APRIL 23, 202011:02

“Activity is peaking on the platforms where it takes place, very similar to how it peaks around holiday time when people are off work,” said Brian Herrick, assistant chief of the FBI’s Violent Crimes Against Children and Human Trafficking Section.

He confirmed that “a lot of activity” took place in coded conversations on mainstream social media platforms, but noted that the “most egregious child sexual abuse material” was shared on the dark web.

It’s too early to see a spike in case openings, Herrick said, as they typically lag behind the online activity.

All the technology companies that NBC News contacted for this article — Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, WhatsApp, Telegram, TamTam and Mega — said that they have zero tolerance for child sexual exploitation and that finding, removing and reporting such content to law enforcement remains a top priority.

Moderation falls short

Most technology companies use automated tools to detect images and videos that have already been categorized by law enforcement as child sexual exploitation material, but they struggle to identify new, previously unknown material and rely heavily on user reports.

Distributors and consumers of this material have developed elaborate, cross-platform strategies to dodge detection. They frequently use the most popular platforms to find a community of child sexual predators to whom they can advertise the material they have using coded language. They then drive interested consumers to more private channels where they can access the material, often using encrypted messaging apps or poorly policed file-sharing services.

Concerned parents notified NBC News of accounts on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and in the comments of YouTube videos where users were sharing and asking for links to child abuse images and videos. Many of the links were to groups on private messaging apps including Telegram and WhatsApp as well as to file-sharing sites such as Mega. Sometimes they used generic terms with the initials “C.P.,” a common abbreviation for child pornography, such as “caldo de pollo,” which means chicken soup in Spanish. Others made references to the names of children who appear in sets of child abuse imagery already known to law enforcement. NBC News did not click on the links to verify that they contained what they advertised.

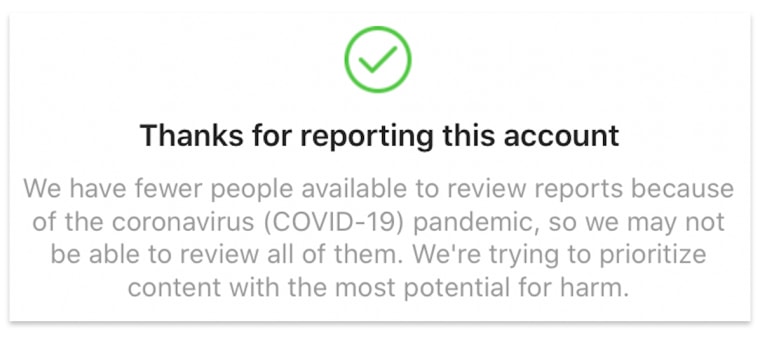

Technology companies are already under immense pressure to reduce the spread of misinformation related to COVID-19 on their platforms with fewer workers available to review content because many contractors have been sent home and cannot access the company’s systems remotely due to security issues. Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have each created warnings thatthey might be slower than usual to respond to reports when users flag an account or post for review.

YouTube said in a blog post that it is relying more heavily on technology to do the work usually done by human reviewers. All companies said they continued to prioritize child sexual exploitation material in their content review processes.

The issue is compounded by several factors during the pandemic, say experts from law enforcement and child safety groups. People are generally spending far more time at home and online, giving them more time to look for and distribute content of all sorts, including child sexual exploitation material.

Because of school closures, there are also more children at home, which leaves them more vulnerable to sexual exploitation by family members or those online, the FBI warned last month. However, there are also more people online to find and report material, which may add to the workload of tech companies’ content reviewers and those at the national cybertip lines.

‘There’s nobody watching’

Parents of underage Instagram influencers said there has been a palpable shift in the number of predators trying to make contact.

“The past several weeks have been a s—show,” said Katie Spinner, a Los Angeles-based teacher who monitors the Instagram account of her 16-year-old daughter, Lily, a model and influencer.

Even before the pandemic, Spinner would field direct messages from older men who would make lewd requests or send photos of their genitals. However, over the last few weeks they’ve been emboldened.

“I’ve seen seven erect penises this week in profile pictures. People have realized there are no controls right now. There’s nobody watching,” she said, noting that Instagram has been less responsive to her reports during quarantine.

Concerned parents of children on Instagram pointed NBC News to a network of accounts showing legal pictures of young children in provocative poses and descriptions linking out to private messaging groups or other channels. One account depicted prepubescent boys in underwear or swimwear, some of whom were sleeping, with a lewd caption on every picture inviting the reader to sexually abuse the child.

“These types of images are inappropriate but they don’t meet the threshold for child sexual abuse material,” said Sarah Smith, a technical researcher at the U.K.’s cybertip line, the Internet Watch Foundation. “We typically see this type of content on gateway sites that may also contain illegal content.”

NBC News reported the account through Instagram’s in-app reporting feature, along with several others. The Instagram app responded with a message stating that the company couldn’t “prioritize all reports right now” because it had fewer people available to review reports because of the pandemic. “So we’re only able to review content with the most potential for harm,” the message said, suggesting muting or blocking the account in the interim.

Instagram said that some of the content review work had shifted from contractors to full-time employees, but that those employees were highly trained on the platform’s content policies. The company’s capacity to review child sexual exploitation material remained unchanged, it said.

On Twitter, hashtags that child protection groups and online activists have been reporting months and flagged to NBC News, such as #MegaLinks, continue to be used to advertise or ask for “C.P.” links or groups on Telegram, WhatsApp and other platforms including Mega and messaging app TamTam. Some users shared links publicly or made offers to share links to people who sent them a direct message. NBC News did not click on the links or interact with any of these users.

Mega Chairman Stephen Hall said that the company has “zero tolerance” for child sexual abuse material and immediately disables links to files shared on its platform, closes the user’s account down and shares account details with the New Zealand authorities, where Mega is headquartered, when it receives a report.

In the first three months of 2020, Telegram has taken down 26 percent more groups and channels for child abuse than it did over the same period in 2019 — 18,815 compared to 14,950, according to data it releases online each day. April is on course to be its largest ever month for takedowns of these kinds of channels.

A pandemic push

To meet the increased demand for new material, more children are being sexually abused on camera, experts say.

“Child sex offenders are not satisfied viewing the same old materials over and over again. They want to see new photos and videos of children being sexually abused with escalating violence,” said John Tanagho, a field office director for the International Justice Mission, a nonprofit that helps rescue children in the Philippines from being sexually abused on demand by Westerners via livestreams.

New material is sometimes created on demand in exchange for payment. This material is often recorded and subsequently distributed as videos or still images.

These livestreams are “the engine” that creates child sexual abuse material, Tanagho said. Although it’s difficult to measure because the platforms lack the tools to screen livestreams, he said there are “very strong indicators of a spike” in livestreamed child sexual abuse. Cybertips of child sexual exploitation in the Philippines, including the distribution and consumption of material, tripled in the first three months of 2020, corresponding with the global lockdown.

“With COVID-19 it’s a perfect storm. Traffickers are on lockdown in the Philippines. Victims are not at school,” Tanagho said, noting that in more than 60 percent of cases the local trafficker is a family member or close family friend.

He called for technology companies, including social media sites, messaging apps and livestreaming services, to make more of an effort to detect when children are being abused via livestreams on their platforms. “That’s where the abuse is being facilitated. What they can see, law enforcement can’t see,” he said, noting that tech companies could combine AI tools with human content reviewers to help ensure victims are rescued sooner.

“It really comes down to a choice,” he added. “If they choose to prioritize child protection, they will detect the exploitation as it’s happening and that means children will be rescued days or weeks or months after the abuse as opposed to years.”