Misinformation surrounding PIDs in Hurricane City: Mayor Nanette Billings rallies landowners, developers, council members, and community to understand the facts

(Hurricane City Council Meeting, Hurricane, Utah, Feb. 9, 2022 | Photo Courtesy of stgeorgeentrepreneur.com)

Misinformation surrounding PIDs in Hurricane City: Mayor Nanette Billings rallies landowners, developers, council members, and community to understand the facts

By Elainna Ciaramella

Washington County, Utah, is experiencing a painful housing shortage, and an unprecedented number of cash buyers including our very own police officers, emergency responders, teachers, and food and beverage workers are struggling in what has become bidding wars. In order to retain our very own southern Utah residents, we must fix the county’s infrastructure issues that must be strategically solved and fast, or else.

COVID-19, is an additional driver, but isn’t the only factor behind Washington County’s troublesome housing shortage. It is recommend that anyone concerned about the current housing crisis familiarize themselves with a report released by the National Association of Realtors® (NAR) and authored by the Rosen Consulting Group, which points to decades of underinvestment and underbuilding (since the Great Recession) for creating a drastic housing shortage nationwide.

“Perhaps most critically, the extreme shortage of for-sale inventory contributed to an untenable scenario in which robust demand is competing for a limited supply, driving housing prices higher, reducing affordability and making homeownership less accessible for low-and-moderate-income households,” according to the report.

As Washington County residents, we must be proactive, and improve the supply shortage with smart growth, but the more important question is, how?

As a journalist who regularly covers real estate and law, I pondered Washington County’s explosive growth and most importantly, the urgent infrastructure demands it brings. Research led me to one solution — Public Infrastructure Districts (PIDs), passed in Utah in 2019 under the Public Infrastructure District Act, Title 17D, Chapter 4, a target of harsh criticism from a Hurricane City councilmember.

What is a public infrastructure district?

Randall “Randy” Larsen is a shareholder-director at the law firm of Gilmore & Bell, P.C. in Salt Lake City where he works in all aspects of public finance, including economic development. Larsen and his colleague, Aaron Wade, had a significant role in drafting the Utah Public Infrastructure Act.

“Probably even more important, was educating the legislature and other critical stakeholders on creating a financing tool that is similar to other states, but more conservative as appropriate to Utah,” said Larsen. Larsen explained that a PID is solely a public financing tool allowing new growth or development to pay for its related government-owned infrastructure, independent from the rest of the city or county.

PIDs, he said, may collect a higher but limited property tax or impose assessments in their boundary to finance such public infrastructure. As a separate entity, the PID’s obligations or debts are separate and expressly not the debts or obligations of the creating city or county.

“PIDs are created at the discretion of the city or county and also require 100% consent of all property owners in the proposed PID. They cannot be imposed on any unwilling property owner.

“By statute, PIDs cannot compete with cities, counties, or other districts in providing public services or owning public infrastructure typically owned by such entities. PIDs intentionally have no land-use authority (planning, zoning, or density), the city or county maintains all control over that.”

Larsen says PIDs allow new growth areas of a city or county to pay for its impact on public infrastructure needs (roads, water, sewer, etc.) without burdening the city or county government or residents with such costs, especially those public improvement costs that cannot be perfectly captured by impact fees.

Hurricane City councilmember expresses concern about PID abuses

While evaluating the benefits of PIDs and how they can help solve Washington County’s infrastructure concerns, I had to consider the naysayers of PIDs, particularly mentioned in a December 2021 St. George News article, “Boon for growth or ‘double tax’ on residents? Hurricane council divided on public infrastructure districts,” which dives into the strong opposition of one Hurricane City councilmember, and the argument this individual presented to the Hurricane City Council against PIDs in a three-page document entitled, “Concerns About PIDS.”

In the spring of 2021, the Hurricane City Council approved three public infrastructure districts (PIDs) for the Gateway at Sand Hollow with a 3-2 vote. The three PIDs had to be individually approved by a majority council vote, and in each case, the author of the three-page document voted nay.

The councilmember’s stark opposition against PIDs was covered in the previously mentioned St. George News article, leaving me to question the validity of the claims. For Washington County residents, myself included, to arrive at a logical conclusion, it’s necessary to take a closer look at what PIDs are, what they do, and how they work — and I went straight to the experts.

Better master planning for the future

“As PIDs aid the overall capital stack of new development, they can also allow for better master-planning and amenities for new development as may be mandated and considered by the city or county. PID bonds typically qualify for federal income tax exemption on the interest earnings and therefore provide the lowest cost of financing available,” said Larsen.

Larsen said the first PID was used in conjunction with a significant medical school facility in Provo, Utah with significant remediation costs from a former city dump. Since then, PIDs have been issued for significant public infrastructure projects (roads, underground parking structures, regional traffic mitigation, water lines and storage tanks, etc.) across the state and many others are underway.

However, PIDs are not a “one-size-fits-all” development tool. All cities or counties should review a proposed PID in light of the master planning and other custom objectives of the city or county. Finally, transparency to future potential property owners in a PID is also critical and was an important principle of the PID Act.

Brennan Brown is a managing director with D.A. Davidson Companies’ Special District Group, a full-service investment bank, where he holds an executive leadership position to direct and grow the firm’s industry-leading special district work.

Brown’s extensive experience analyzing, structuring and investing in special district debt across the country has led their Special District Group to the successful completion of more than 100 transactions, totaling more than $2 billion in public infrastructure investments over the last 12 months.

“In the state of Utah, we have raised approximately $250 million for public infrastructure improvements across Utah’s communities through the use of Public Infrastructure Districts (PIDs),” said Brown.

Brown explains how PIDs are an entity formed by Utah cities and counties to finance public improvements, through the issuance of municipal bonds. This financing can pay for public costs, including street improvements, traffic and safety controls, water improvements, sanitation improvements, storm water drainage improvements, parks and recreation improvements and other civic amenities, he said.

PIDs for smart, not rapid growth

Brown says infrastructure financing is one of the key challenges in a rapidly growing state. Many cities and counties across Utah are feeling these growing pains and often lack the necessary funds to build the infrastructure needed to keep pace with that growth, he said.

Brown’s team specializes in raising capital early utilizing PIDs, which build infrastructure ahead of growth, minimizing the growing pains of fast-growing jurisdictions while effectively accommodating the new growth.

The other advantage, he said, is the infrastructure is paid for by those incoming developments rather than the community as a whole. This also helps alleviate the burdens placed on the budget of local jurisdictions.

According to Brown, a PID can finance using various repayment mechanisms. The two most common are a limited property tax and a special assessment:

- A limited property tax is an additional property tax imposed by the PID on landowners within the boundaries of the PID. As all landowners are required to give their consent to join a PID, they are agreeing to the additional property tax upfront. This additional property tax is limited by both state statute and the governing document of the PID. There is no way to prepay a future property tax, so if a PID finances using a limited property tax as the repayment mechanism, there is no way to prepay the PID bond. Therefore, the property owner will be on the hook for this additional property tax until the bonds are repaid (typically the maturity of the bonds is 30 years).

- A special assessment is a fixed annual assessment levied on a property that benefits from the public infrastructure improvements the PID finances. Because this payment is fixed through the 20-year lifespan of the bonds, there is a way to calculate a prepayment at any time at the request of the property owner. The advantage to the property owner is they may choose to make the prepayment at any time. A drawback to this type of mechanism is that the capital markets and investors typically don’t like to invest in bonds with a short maturity.

Introducing the Black Desert PID

Many residents in Ivins, Santa Clara, and the rest of Washington County have heard the buzz surrounding the Black Desert development, and are excitedly awaiting its roll out. In September 2021, Brown’s team successfully priced and closed $106 million of limited tax general obligation bonds for the Black Desert PID.

The proceeds will be used to fund public infrastructure for a commercial and residential resort community in Ivins known as Black Desert Resort. “Black Desert will be a transformational, amenity-rich community, designed as a vacation destination for guests and visitors, as well as a home for full-time and part-time residents.

“The community is anticipated to become a substantial economic driver for the

southern region of the state, with phase one of the development expected to create

approximately 500 new jobs and future long-term employment opportunities. Without district financing, balanced, sustainable and visionary projects like Black Desert would be tough to accomplish.”

In 2020, Brown’s team achieved the first bond issuance from a Utah Public Infrastructure District, a significant milestone not only for their team, but the entire state of Utah. Those bonds financed the public infrastructure needed for the development of a new medical school in Provo, the Noorda College of Osteopathic Medicine, that will serve the state of Utah and become an economic catalyst and asset to the entire region.

Brown says that in the medical field, individuals tend to stay in the state where they are trained. As Utah’s population continues to expand, the need for physicians continues to increase with it, and through their team’s commitment to supporting future generations through the power of public financing tools, D.A. Davidson’s successful transaction for the development of a medical campus will generate employment opportunities that encourage students to become full-time professionals in-state after graduation.

He says funding new healthcare infrastructure projects supported by a PID not only provides opportunity to train and educate up-and-coming medical professionals, but encourages them to live and work in their communities.

How PID financing works

Authorized by the enactment of Utah S.B. 228 in 2019, PID financing can only be used for public infrastructure, such as water and street improvements, traffic and safety controls, sanitation improvements, improvements to storm water drainage, parks and recreation improvements, as well as other civic amenities.

A PID Limited Tax Bond is a local government financing tool that imposes an additional property tax levy on future users of the infrastructure for the purpose of repaying the debt issued to finance the infrastructure. This is limited to a 15-mill maximum levy unless the creating entity (city or county) adopts stricter guidelines, and it must mature within 40 years of issuance. For an in-depth look into PIDs, read this PDF fully explaining Public Infrastructure Districts.

Karl Rasmussen is the president of ProValue Engineering, a consulting firm in Hurricane, Utah, that specializes in civil engineering services, project management, and construction staking. He pointed out one of the benefits of PIDs: the total buildout of infrastructure is available.

When a PID is set up, the district can install bike and pedestrian trails, parks for recreation, public safety buildings, and more enhanced public infrastructure. “This isn’t available without a PID,” he said.

Without a PID, he explained, there could be piecemealing of roadway and infrastructure improvements that could lead to further need for city resources to finish missing sections of the city infrastructure. In the absence of a PID, one will see new roads being cut up and new utility lines installed in order to sustain the larger infrastructure.

Misconceptions about PIDs

Argument: PIDs are doubling or tripling the value of land without developers paying a penny, developers, who in many cases are landowners wishing to do something with their private property with a developer.

Conclusion: The developer and/or landowner is pledging the most expensive line item when developing land, the land itself. When a landowner enters into a PID, their property is encumbered by the PID and the developer–landowner is required to pay the special assessment as long as he or she owns the land. The land is just a portion of it.

The PID mostly covers regional style infrastructure and public amenities. The cost of the street level improvements is 10X the amount of the PID over time. That is the street and house level roads, water, sewer, utilities, etc. The city still retains 100% rights on determining zoning and development approvals.

If he or she doesn’t pay the assessment, the PID can foreclose on the developer–landowner, the same as the end consumer. The developer also pays for engineering, preliminary plans and concepts, soil testing and will spend countless hours bringing a group of landowners and developers together in one singular collaborative effort.

The value of the land will increase by default with the improvement of the land; for example, utilities, curb, sidewalk, drainage, and additional amenities such as club houses, dog parks, community gardens, and swimming pools.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: PIDs wrongfully shift risk and it’s customary for developers to invest and take the necessary risks to enjoy the back-end profits. The developer’s risks are largely mitigated, leading to increased profits for developers, and there would be no discount on the purchase price.

Conclusion: The developer–landowner would need to be competitive in the market. The lot sale will be hinged to the market and what the market will bear. It, of course, would be subject to LTV’s (loan to value by banks if the end consumer is borrowing funds), and comparables by real estate agents representing their clients. If the end consumer can purchase a lot for less money across the street with the same amenities, then why not do so?

The PID actually reduces the city’s obligation as much as, or more than, the developer. The PID passes off the city’s obligations for regional infrastructure at a benefit to the city and current tax payers who do not pay on the new PID. PIDs are great for existing owners as they are not burdened by new growth by new taxes or city bonds.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: PIDs involve a sneaky tax driven by developers.

Conclusion: PIDs represent a special assessment. However, PIDs can work similar to a property tax because the assessment may be based on a rate per $100 of value of property. Public Infrastructure District Act S.B. 228 states the bill “imposes a limit on a property tax levy for the operation of a public infrastructure.” The PID acts as a full disclosure to the city and the public.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: The end consumer has no idea of the special assessment.

Conclusion: While this was an issue when the law was first introduced, it has been corrected and is no longer a problem. The PID is now disclosed multiple times to buyers prior to closing (e.g. realtor, seller disclosures, good faith estimates, and settlement statements among other legal instruments). Additionally, the appraisal and lending institutions disclose the mortgage payments and appraisals keeping this in check. The councilmember is extrapolating data from an old ordinance and outside of the state of Utah.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: PIDs are unfair; people across the street aren’t paying extra tax, so what extra benefit does a PID homeowner receive in exchange for the extra tax?

Conclusion: The PID is an assessment; the PID improves the lot and by default, adds value to the land. If an informed buyer chooses to pay a premium for the location and amenities they prefer, is it right for the city to interfere with that choice?

It is the city’s duty to ensure the buyer is informed in advance of the purchase. That is the only real issue, and is relatively easy to accomplish. There are many ways to ensure all generations of future home owners provide the required notification when they go to sell the house.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: PIDs give irresponsible control to a self-interested developer board. They create annexation issues and abuse of authority.

Conclusion: The board is the landowners, and the PID policies and the creation thereof are controlled mainly in part by the city council within the PID jurisdiction. Annexation from other land owners wishing to join the PID would pay their allocated share.

The board is subject to audits based on the policies and laws of the PID. There have been such abuses in Colorado, but in Utah, the board and the city have oversight.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: PIDs jeopardize the ability to effectuate tax increases–bonds in the future, assuring PID participants will strenuously resist and half the town (the new portion) will be subject to PIDs.

Conclusion: The only citizens subject to the PIDs are those who choose to purchase a lot within the PID district. This is a benefit to existing citizens and highly reduces the likelihood of future tax increases that otherwise would be normal with a growing city.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: If PIDs are approved for the south end of town, it will facilitate the speedy rollout of numerous developments contrary to the desire of residents. The document said growth for growth’s sake is the ideology of a cancer cell and if our small town is transformed into a large city, we’ll lose heritage and small town charm.

Conclusion: NAR says we are 5.8M housing units short on a national scale, and we have seen the largest increase in prices in history. Does the councilmember only want millionaires to live in Hurricane? Because, that is what his proposed policy would result in. It squeezes out the citizens we love and enjoy. Ivins recently approved zone changes on the basis that housing costs are the majority concern at the present time.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Furthermore, if the PID is approved south of town, it will bring a collaborative effort of landowners, developers and the city together to ensure the infrastructure is rolled out effectively, responsibly and appropriately to allow for future growth.

Argument: Citizens do not want growth.

Conclusion: The councilmember did not include any polling data with his statement. It is fair to suggest that citizens are equally concerned about housing affordability and without responsible growth, the supply gets squeezed as demand increases, thus the housing market keeps going up considerably. There already exists a major shortage of building lots in Washington County; with an increase in supply the prices will go down as demand is met. To stunt growth specifically in this area mitigates the rights away from landowners wishing to execute their private property rights to use their land according to the existing master plan and zoning within the city.

We look to Sedona, AZ as a cautionary tale, one that sees no immediate relief in sight. Currently, businesses large and small in Sedona are struggling to keep and find employees who are fleeing to more affordable places. Washington County is already struggling with unaffordable housing, would disorderly growth and rising housing prices be good for our economy?

“From what we hear from businesses who need to fill positions and keep workers, and workers who work in our businesses, it is a crisis,” said Linda Martinez, a business owner in Sedona and former chairwoman of the defunct Sedona Affordable Housing Commission.

“This issue is at the heart of who Sedona is as a diverse community animated by the arts and our environment. The people who work in these fields cannot afford to live here. Should that matter? It should since local workers are the backbone of our economy, schools, and service and critical providers. We also cannot separate increasing traffic from workers driving in from surrounding areas and [having] to go across town to work.”

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: Growth is much faster than residents prefer.

Conclusion: The councilmember did not enclose any recent polling data with his three-page article. However, most residents want the small town charm, but also want affordable housing where their children can live nearby. Responsible smart growth helps accomplish both and rejecting the PID is denying the landowner from developing his or her property within the current zoning, which Hurricane City Mayor Nanette Billings has gone on record saying she will help if it meets the current zoning.

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Argument: History of problems citing Colorado as an example.

Conclusion: In the councilmember’s document, he cited a December 5, 2019 article in The Denver Post, shedding light on abuses of Colorado metro districts and how developers were sticking homeowners with soaring tax bills. In Colorado, when metro districts were being created, the concern was that the only voters were the developers, their spouses, and a handful of their business associates.

The above is valid and addressed by Utah’s law, which states that a public infrastructure district may issue a limited tax bond in the same manner as a general obligation board, with 100% consent of surface property owners within the PID boundaries and 100% of the registered voters, if any, “within the boundaries of the proposed PID, or upon approval of a majority of registered voters within boundaries of the public infrastructure district voting in an election for that purpose under Title 11, Chapter 14, Local Government Bonding Act.”

https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title17D/Chapter4/C17D-4_2021050520210505.pdf

Denying the PID will only force the developers to act independently. A denial may stunt growth for a short time, but the growth is coming. We want to keep our small town charm but also grow in a responsible way.

If citizens were polled about home prices in the area, there is no doubt they would complain about high housing costs. They would also complain about the constant construction and roadwork. Approving PIDs will alleviate both.

With Dixie Springs, for example, the rollout of the roads and utilities were quick but the subdivision took years to build. Today, Dixie Springs is still not 100% built out, but it’s a great case study for PIDs as it was responsible growth and created much of the affordable areas to buy a lot in the Washington County area.

No growth equals stagnation and it squeezes out the very citizens we love and enjoy, including our posterity of younger millennials and Generation Z groups. Placing a handful of PIDs in Washington County is barely a transformation from small town charm to a big city as naysayers claim.

Hurricane City has approved three PIDs. To deny others from the same privilege would be discrimination, not giving other property owners the same rights and privileges. It also sends a statement to landowners that Hurricane City would rather make it difficult for you to develop your private property under the current zoning that it allows.

PIDs enhance a community’s amenities

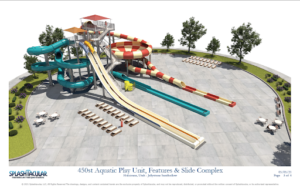

Utah has commercial and residential PIDs, which are great for the end consumer and the developer. Why? Developers can offer a better product because it is not costing them millions to bring in the infrastructure, therefore they can provide nicer amenities, as proven in the case of Zion Utah Jellystone. The resort is underway in the Gateway PID.

(Gateway PID at Sand Hollow, Glampers Inn RV Resorts, LLC | Photo Courtesy of Scott Nielson, CEO of Glampers Inn RV Resorts)

(Gateway PID at Sand Hollow, Glampers Inn RV Resorts, LLC | Photo Courtesy of Scott Nielson, CEO of Glampers Inn RV Resorts)

(Gateway PID at Sand Hollow, SplashTacular | Photo Courtesy of Scott Nielson, CEO of Glampers Inn RV Resorts)

(Project without a PID, Washington City, Utah, March 9, 2022 | Photo Courtesy of stgeorgeentrepreneur.com)

(Project without a PID, Washington City, Utah, March 9, 2022 | Photo Courtesy of stgeorgeentrepreneur.com)

Developers and landowners utilizing PIDs take their duties to their community very seriously. There is a great deal of risk when land owners and developers pledge their land and money to the PID district.

The alternative ― if developers pay most of the expense, each developer will act independently, burdening the city with numerous applications and splicing each development pertaining to their own property to the other. We will have a cluster of undeveloped infrastructure and the city will be to blame.

(Project without a PID, Washington City, Utah, Little Valley area, March 9, 2022 | Photo Courtesy of stgeorgeentrepreneur.com)

(Project without a PID, 3000 East, on the border of Washington Fields and St. George, Utah, March 9, 2022 | Photo Courtesy of stgeorgeentrepreneur.com)

The residential PIDs will provide a nicer, cleaner, smoother development without future hack jobs to our city roads and communities. The PID also allows the city to request other amenities and infrastructure, such as parks, jogging trails, etc. In many ways, PIDs are no different than HOA dues. Would a city council ever suggest you can’t have HOA dues?

This entire country believes in personal freedom and property rights. Why would anyone who is informed object to a financing mechanism that gives the city new improvements and public spaces at no cost or risk to the city, is fully noticed in transactional documents, and allows the buyer to determine if the extra cost is a benefit just like an HOA?

In summary, we can all agree that Washington County is in a housing crisis, and from what I learned, PIDs are an excellent solution. They pave the way for regional infrastructure without imposing a financial burden on existing residents and cities. They reduce the need for new taxes and bonds, provide regional trails and parks at no cost to the city, and build major improvements that would otherwise need to be bonded.

PIDs facilitate long-term planning to avoid the traffic nightmares of other cities that turn a blind eye and deny. Further, they expand the availability of residential units, creating competition to alleviate the explosive costs of housing that’s been pricing out our children and grandchildren.

About the Author

Elainna Ciaramella is a native of Los Angeles, but spent over a decade by the beach in South Orange County, California. After moving to sunny Las Vegas, the “Entertainment Capital of the World,” her yearning to live closer to an outdoor playground brought her to southern Utah, where she now lives a few short miles from Tech Ridge, Atwood Innovation Plaza at DSU, Dixie Technical College, and some of the best trails in the Beehive State. As a researcher, journalist and hopelessly devoted storyteller, she has spent many full days and long nights interviewing business owners, researchers, CEOs, and C-suite executives from all over the country. Her curiosity is endless and she is constantly seeking information that will intrigue and inspire readers.